Thursday, December 6, 2012

Smart input

The early development of software for emailing, web-surfing and texting in Asian languages was hindered by the variety and complexity of writing systems. Asia has by far the largest share of the world’s scripts. These include ideographs (traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese, simplified Japanese); syllabaries (Japanese, Korean); complex alphabets (Tamil, Thai ); alphabets written from right to left (Arabic, Hebrew) or top to bottom (Mongolian); and adaptations of the Roman alphabet with special diacritics (Vietnamese). Several languages have changed their scripts, such as Kazakh, which used Arabic characters until these were replaced by Cyrillic under the Soviet Union, and is now being written more and more in Roman letters. Different software programmes encoded scripts in different ways, and so even if you could write your native language on one computer you could not necessarily do it on another.

This problem has largely been solved by the development of Unicode, which assigns a unique number to each character. Adopted by global companies such as Adobe, Apple, Google, IBM and Microsoft, it is supported by most web-browsers and important programming languages like Java. Thanks to Unicode, Balinese and Cambodians can word-process in their traditional scripts. Characters added in 2007 include the Tibetan /rra/, archaic digits found in Sinhala texts, and the Sundanese script. Bhutanese can write Dzongka using Tibetan-based software.

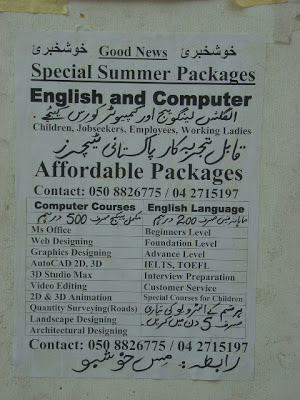

Although it is now possible to write almost any Asian language, some people still feel that to use a computer it is necessary to know the Roman alphabet, and preferably, the English language. A few years ago I met a student in Lahore in Pakistan, for example, who regretted not being able to email his father down in Karachi because the latter did not know English.

One reason for the continued association between English and computing is the way people originally learnt to use technology. I have several Thai friends who started using computers when the only available programmes were in English, and they became so used to using English for emails that some of them continue to do so, even when writing to Thais. Of course they all know that it is possible to write Thai on a computer, but some of them tell me that it is still quicker for them to use English. Perhaps it is because we only need about 30 keys for English (the 26 letters and the space-bar, return key etc.) whereas to write the 70+ letters of the Thai alphabet nearly every key on the keyboard must be used both in lower case and in upper case mode.

However, even where people decide to use Roman-script input, difficulties may arise because of all the different romanisation systems. Whereas these are relatively minor in Japanese (sho vs syo, for example, or tsu vs tu), the pinyin favoured by China and Wade-Giles system preferred in Taiwan can produce discrepancies such as Gaoxiung vs Kaohsiung and gong fu vs kung fu. The name pronounced /ri/ in Korean can be Li, Lee or Rhee. In Thailand almost every language school seems to have its own way of Romanising the national language – which is very frustrating for foreigners trying to learn it. Japanese has only 50 syllaberies (in two forms of kana: hiragana and katakana) and the keyboard of most Japanese computers (including the one I am writing this on) can easily cover them if we include the number keys in shift mode. Nevertheless, all the Japanese I know input their writing in Roman letters, even though the output appears in a mixture of Chinese characters and kana. This is the same with Chinese. Nearly all Chinese computer users input pinyin (the Roman alphabet adapted to Chinese sounds) to obtain a large choice of characters appear on the screen. We can therefore say that even if Thais and Koreans can do without Roman letters, Chinese and Japanese cannot.

As for writing messages and emails on telephones, this has changed dramatically since the spread of smartphones, which have keyboards similar to computers. A few years ago there used to be competitions for writing messages using the number pads only, and some people – especially young women – seemed to be amazingly fast. Their speed was enhanced by predictive spelling, which anticipates and tries to complete what you are about to write before you have finished it, and this software was especially advanced for Japanese. If I write Japanese on my old phone it is much quicker for me to use Roman-character input than kana input (but of course it is quicker still if I can write in English). In fact, even though I have been using a smartphone for over a year, I still carry my old phone sometimes (for example, when I go jogging), and I think I can input just as fast on its number pad than I can on my smartphone’s keyboard – especially since I find the latter too small for my fingers and often make mistakes!

Many of my older Thai friends use Roman script input on their phones even if they write Thai. Some of them who are using older phones say that it is almost impossible to input Thai characters on a phone because every number key needs to support about seven different characters. Even some Thais with smartphones input using Roman script for the same reason that they do so on their computers – they find an alphabet of 26 letters easier than one of over 70. One friend told me that another reason for inputting in Roman letters is because it is cheaper. He added that since most Thais cannot read Thai written in Roman letters, he tends just to write in English. Another Thai friend told me that even though she usually writes in Thai and she uses Thai character input to do so, she mixes her Thai messages with a lot of English words and expressions. However, I hear that a lot of younger Thais are now texting using Thai characters. I don't know if they add Roman characters (e.g. btw, CUl8r) or English expressions (YES, OK), but I do know that this is quite common among young Chinese and Japanese.

There is no doubt that it is now much easier than before to use Asian scripts on computers and phones. But this brings up a question: what happens when people whose language is written in a complex script such as Chinese characters do not have their computer or phone available? I know in my own case that although it is pretty easy for me to write in Japanese on my computer, if I have to write a letter by hand, or write something on the blackboard, I often find that I suddenly cannot remember how to write certain characters – even quite easy ones that I would never forget how to read. Of course I did not learn Japanese when I was young, so it is inevitable that the characters are not as firmly embedded in my head as they are for Japanese people. But some Japanese friends tell me that they too sometimes forget how to write a character when they don’t have their computer. However, since Japanese is written in a mixture of Chinese and kana (and even roman script), if you don’t know a character you can generally write it phonetically.

But as far as I know, if you forget a Chinese character it doesn't look very good if you just write it in pinyn. So I wonder what Chinese people do when they forget a character? Or maybe they never forget?

Friday, November 30, 2012

Technical support

Last month I wrote about call centres. One of the jobs many call centre employees have is to provide technical support for people who can’t assemble or operate some product. In many cases they are providing English-language support for consumers who have bought products made in Asia. China now dominates the production of all kinds of electronic equipment and this has generated a huge demand for technical translators, with English the language most needed. But the English instructions that come with products are often baffling (“For safety reasons do not put the air-conditioning in the chicken”) as well as sometimes being entertaining (“Please to insert card in your mother’s board.”).

As a general rule, translation should be done from a foreign language into the translator’s own language, but the rapid pace of Chinese economic growth, and the lack of English-speakers learning Chinese (in comparison with Chinese learning English) means that mostof the English translation is done by Chinese, and some if it is not very good. Of course this is not just a Chinese problem. Not so long ago I was staying at a hotel in Nagoya and the instructions for using the TV were: It is able to be seeing of the program of the favorite by pushing ground D button and pushing the channel button in the TV operation part when switching from the room theater to the TV screen. This was clearly produced using translation software and somehow I worked it out. In fact I should add that I generally find both the English and the Japanese instructions for Japanese products much better than their British or American ones. I should also mention that my mother, who did not learn to use a computer until she was 70, found the advice she received from a call centre based in India extremely clear.

Of course translation software, such as Googletranslate, has improved greatly. But just like an old-fashioned dictionary, it has to be used carefully and intelligently, and is likely to lead to disastrous results if used by someone who doesn’t know the language they are attempting to translate at all. Asia’s achievements in both hardware and software production seem all the more impressive when we consider the language barriers that have had to be overcome. Much of the technology in use today was originally developed by scientists working in English.

The first modern computers (Iowa State University’s Atanasoff and the University of Pennsylvania’s ENIAC) were built in the United States. Briton Tim Berners-Lee has been credited with inventing the worldwide web. The first text message was sent in the UK. A lot of technology has also been developed by scientists who were not native English-speakers yet worked mainly in that language. Thus the generation of Asians that started to use personal computers in the 1980s or send text messages in the 1990s tended to do so in English. But now Asians lead the world in both software and hardware production.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Call Centres

Recently I’ve been having one or two problems concerning a bank account I have in Britain. I have several numbers for the bank that look like British phone numbers. But whenever I call, I am answered by someone in a call centre in India. This has caused me some difficulties since the problem I have really needs to be resolved by someone who is actually in the UK, yet none of the people in India seem to be able to give me a contact number for anyone in Britain. However, I hasten to add that the people at the call centre themselves are quite competent and I can certainly understand their English. Indeed it is often easier for me to understand them than people in certain parts of Britain where they have a distinct regional accent. Because salaries for Indian companies are still relatively low, call centres there which serve international companies tend to attract employees with excellent English and high educational backgrounds. Offshore call centres (or contact centres) are the best-known face of business process outsourcing (BPO), a rapidly growing global phenomenon whereby companies transfer work to somewhere with lower labour costs. Outsourcing may be onshore: many Japanese companies, for example, use call centres in Okinawa where wages are lower than in Tokyo or Osaka. But they save even more money if they offshore services to China, where it is increasingly possible to find workers fluent in Japanese. Asian countries that have high levels of English are particularly well-placed to attract outsourced work from the huge number of companies doing business in that language. According to India’s Economic Times, BPO is now moving into higher-value KPO: ‘knowledge process outsourcing’. In the Philippines, the work done by call centres includes software development, animation for Hollywood feature films, and transcription of legal and medical documents. If you check a job-recruitment website such as mynimo.com you will find hundreds of positions being advertised for dozens of BPO and KPO offices in Cebu City alone. The Philippines has even been getting work from India. In India itself, a growing outsourced business is tutoring for children. In the United States, face-to-face tutoring for a high school student can cost up to $100 an hour, whereas an online tutor based in India can be found for as little as $2.50. Bangalore-based Tutor Vista has 150 tutors advising 1,100 children in America. Parents pay $100 per month for unlimited hours. Tutors have an average of ten years of teaching experience behind them, most have master’s degrees, and they get 60 hours of training in American accents and young people’s slang. Rival company Growing Stars Inc. teaches subjects like elementary school maths, science and English grammar and high school algebra and calculus to over 400 American students. Call centres around the world are often manned by young, single workers who don’t mind working at night. According to Kingsley Bolton, a sociolinguist at Hong Kong's City University, in many Asian countries the job tends to appeal to middle class females who have few safe and socially acceptable work options.Women are often thought to have better language skills and more empathy when dealing with difficult customers. Bolton’s research in the Philippines also found a disproportionate number of gay and transsexual employees who, he speculates, may be attracted to a job that can entail an element of role-play: as long as it facilitates business, phone operatives can be whoever their clients imagine them to be.

This role-playing is highlighted in One Night at the Call Centre, a novel by investment banker Chetan Bhagat that sold over 100,000 copies within a month of its release in India in 2006. The story takes place over a single night at an Indian call centre servicing American appliance users. The main characters have false American names (Shyam is “Sam”, Radhika is “Regina”) and loathe having to be servile to customers they consider less intelligent and educated than themselves. Their instructor advises them to think of 35-year-old Americans as having the same IQ as a 10-year-old Indian. Nowadays nearly everyone knows that a call to New York or Sydney may well be answered in Chennai or Cebu, so the call centre workers don’t need to pretend that they are anywhere they are not. Last time I called my bank I had a nice chat with a man called Sayed about a local Muslim holiday in southern India. He promised to call me back after the holiday with good news about my enquiry – but I am still waiting!

This role-playing is highlighted in One Night at the Call Centre, a novel by investment banker Chetan Bhagat that sold over 100,000 copies within a month of its release in India in 2006. The story takes place over a single night at an Indian call centre servicing American appliance users. The main characters have false American names (Shyam is “Sam”, Radhika is “Regina”) and loathe having to be servile to customers they consider less intelligent and educated than themselves. Their instructor advises them to think of 35-year-old Americans as having the same IQ as a 10-year-old Indian. Nowadays nearly everyone knows that a call to New York or Sydney may well be answered in Chennai or Cebu, so the call centre workers don’t need to pretend that they are anywhere they are not. Last time I called my bank I had a nice chat with a man called Sayed about a local Muslim holiday in southern India. He promised to call me back after the holiday with good news about my enquiry – but I am still waiting!

Monday, October 8, 2012

Internationalising Asian universities

Last time I wrote about international university rankings and wondered whether they were biased toward English-speaking countries. This time I want to say something about how some Asian countries are trying to attract more foreign students by changing their semesters and increasing the number of courses in English. Previously, American students wanting to study for one year in Malaysia, Thailand and Japan, and Malaysians, Thais and Japanese wanting to study for one year in America might have to take two years away from their home university because of differences in the school calendar. But Malaysian universities have started to change their school year so that it begins in September, coinciding with North America and Europe. Many Thai universities will do the same from next year, and Japan’s University of Tokyo is making similar changes. Despite the improved international rankings of several Japanese universities, such as Tokyo, Kyoto, Tokyo Institute of Technology and Keio, according to JASSO, the Japan Student Services organisation (http://www.jasso.go.jp/index_e.html), only 4% of students in Japan are from foreign countries. The number of fulltime foreign university teachers is also relatively small. Moreover, according to the Ministry of Education, the number of Japanese students studying overseas has fallen by 50% in the last ten years. Many people think that all of this is because English is not widely used in Japanese education. But things may be changing.

Recently, Time magazine’s website reported on new programmes for undergraduates at the University of Tokyo starting this month that will be taught entirely in English. These are open to Japanese students but will include participants from 14 other countries. Other universities with programmes in English include Waseda and ICU in Tokyo and Doshisha in Kyoto. Meanwhile the government’s Global 30 initiative aims to increase the number of Japanese students going overseas. Some people think that these changes may help foreigners more than they help the Japanese, however. Already, thousands of Asian students are getting degrees from Japanese universities and then getting jobs with Japanese companies. Many of them were already fluent in Japanese before they came to Japan, especially in writing, which is somewhat easier if you have a language background in Chinese or Korean. Having studied alongside Japanese students, they are attractive to many Japanese companies when they go for job interviews because they speak Japanese and understand Japanese culture well, but they also speak one or two other Asian languages and English well, unlike most of their Japanese friends. If more courses are offered in English, it may mean that more foreign students come to Japan, not just from East Asia, where Japanese has long been a popular subject, but also from Southeast and South Asia and from further afield. Many of them will go on to become proficient in Japanese and knowledgeable about Japanese culture, even if they study in English, and so they may look for jobs with Japanese companies. It is already hard enough for young Japanese people to get jobs – indeed one of the main reasons many of them say they do not go abroad is fear that they will miss out on the very competitive job-hunting process. Making Japanese universities more international through increasing the number of courses in English may therefore be risky. But with the economy continuing to be sluggish, and English spoken much more widely in booming economies like China, Singapore and Malaysia, it appears to be a risk the government is prepared to take.

Sunday, September 30, 2012

English and the educational arms race

Almost all Asian universities demand some English proficiency. Despite its ambivalent feelings towards English since independence from Britain, Myanmar makes English one of three subjects required to get into university. In Indonesia both public and private universities set English tests, whatever candidates intend to study. Since all Singaporean state schools teach in English, students coming from China take a year of English as a university entrance requirement, even though most of their Singaporean teachers will be Mandarin speakers. And nearly all Japanese university entrants take a test in English – even though they may not need to take one in maths or Japanese language.

Many countries continue to make English study obligatory after university entrance. Most of India’s 272 universities not only have required courses in the language but use it as their main medium of instruction. Uzbekistan allows students to choose among English, German or French, but increasing numbers of institutions – including Tashkent University’s departments of Economics, Management, International Relations and Science – have made English compulsory.

In the University of Laos, levels of English are still generally low, but students have a strong incentive to learn it since a lot of the material in their library is in that language, having been donated by international aid development agencies.

While English has long been the main tertiary medium in former British and American colonies, English-medium programmes are increasing in Japan, Thailand, Saudi Arabia and other countries where the language has no official status. This seems to be a global, rather than an Asian, trend, with over 1500 master’s degrees now being taught in English in non-anglophone countries around the world. But motives for teaching in English vary widely, from lack of materials or teachers in local languages, through desire to increase the number of foreign students, to the need to raise international ranking. Recently, Kabul University announced its intention to teach all subjects in English as soon as practicable, but it is suspected that the main aim is not to further its ambitions to be regarded as “the Cambridge of Afghanistan” so much as to find a neutral tongue and avoid antagonisms that have developed during the country’s policy of using both Dari and Pashtun.

Behind most of the initiatives to go ‘international’ through English, however, lies economics. A few decades ago only a tiny elite could dream of going to an overseas university. Indeed when I was a graduate student at London’s highly multicultural School of Oriental and Asian Studies, I had the feeling that many of the Asian and African students there already knew each other because they had been sent to the same schools in Britain and America by their wealthy families. But nowadays overseas education is a possibility for more people.

Global university league tables have been published by the London-based Times Education Supplement (TES), the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) group (which used to collaborate with TEX, and by Shanghai ‘s Jiao Tong University, Many prospective students study them furiously to see how their local institutions compare internationally. According to British linguist David Graddol there is now an “educational arms race.”

QS and Jiao Tong do not always agree, but both have a disproportionate number of English-speaking institutions in their upper rankings. This has naturally led some people to claim there is a bias toward the English language, and even toward Anglo-Saxon patterns of education, in these university rankings. Whatever the truth of this, it is notable that universities in many parts of Asia, are moving up through these rankings. In 2012 QS ranked the University of Hong Kong at 23 and the National University of Singapore at 25 in the world. Both are English-medium. But the universities of Tokyo, Kyoto and Seoul, which teach very few courses in English. followed them closely in the rankings.

Labels:

Afghanistan,

China,

Economics,

Indonesia,

Laos,

Myanmar,

Singapore,

University rankings

Sunday, June 3, 2012

Letter from Korea

A few days ago I got an email from Yousuke, a Japanese student who is studying for a year in Korea. I thought it was very interesting so with his permission I am posting it today. I just made one or two small changes.

"Hello! I'm now having very interesting days in Korea like having a camp with Korean students and studying economics in Korean or watching difference in culture between Korea and Japan. So, from now, I'll write about what I came to recognize through living in Korea. Politeness I think that Korean has much strong polite words like ‘Keigo’ than Japanese and Chinese. Compared with Chinese and Korean, both of which I studied at University, I think that if looked only at language , I think that Chinese hasn’t much polite language because it is very similar to English. In Korea surprisingly, among very close friends, if they have difference of ages, the younger one must use polite words to the elder! It is also among children. They must use polite language to their parents in Korea. And even if Korean people have any fight with each other, they also use polite words if they are not close nor have the same age friend. If a Korean got married, wife should use polite words to husband even she is elder than him.

"Polite things in language also appeared very much in other behavior in Korea. For example, at a convenience store in Korea, customer usually uses polite language to the shop’s person because they are not close. But it is a really strange thing to a Japanese because most Japanese thinks that customer has a strong advantage to the shop’s person and the customer usually doesn’t use polite words to the shop’s staff even if the customer is younger than the shop’s staff! Korean people have pay attention to use polite words or normal words even if very close person. And if the one suddenly use normally words to the other, it may be a little rude thing to the partner. And I think that there is a different appearance of polite meaning in conversation even if the Korean and Japanese are in same situation.

"The different thing among Japanese and Korean is as below thing: in Korean language, most polite meanings appeared in ‘what something is called and is also in the kind of verb used to the speaking partner. But in Japanese language, polite meaning sometimes appears only in a ‘what something is called’ without appearing in the verb. The relation of parents and children is one example of the situation. In Korean families, the children must use their parents by the proper form of address, but also they must use a term of respect in their verbs. Contrary to that, in Japanese families, although the children usually call their father ‘Otousan’ a meaning a polite word for a father in Japanese, children doesn’t use a verb of respect like ’saremasuka?’, the polite word for ‘do?’, to their parents. In this way, I felt that there are many points of difference between Japanese and Korean about 'polite' in conversation and behavior. I also feel that Japanese arrogant manner of a customer to the clerk is not so good thing and it is a sign that Japanese lose a little by little taking care of other person, I think. Maybe difference of politeness between Japan and Korea comes from strongness of Confucianism in Korea. Like that, I think that religion has a strong effect on one country's language. And apart from religion, like custom also strong effect on language. So Americans don't have terms of respect in language, even Koreans grown up in America.

"By the way, I was really surprised that the average English level of Korean students is very high. In Japan, I took TOEIC test and I usually gets a score of around 700-points. I noticed that in Korea, average skill of using English of Korean students is like me or higher than me! I think that it is higher than in Japan. But through English taking class in Korea, I knew that the student's skill is very high here! And they seems to have almost no difficulties to have a conversation with English speakers. I don't know why they are so skilled English even though maybe they don't have so many times to touch with English speakers compared to me. And I honestly felt that their hearing skill is averagely very high . For example, even when I can't understand the English teacher's order in English, almost every Korean student understood it after only one hearing. I felt that it is a sign of how Korea is using the power of English education compared to the Japanese."

"Hello! I'm now having very interesting days in Korea like having a camp with Korean students and studying economics in Korean or watching difference in culture between Korea and Japan. So, from now, I'll write about what I came to recognize through living in Korea. Politeness I think that Korean has much strong polite words like ‘Keigo’ than Japanese and Chinese. Compared with Chinese and Korean, both of which I studied at University, I think that if looked only at language , I think that Chinese hasn’t much polite language because it is very similar to English. In Korea surprisingly, among very close friends, if they have difference of ages, the younger one must use polite words to the elder! It is also among children. They must use polite language to their parents in Korea. And even if Korean people have any fight with each other, they also use polite words if they are not close nor have the same age friend. If a Korean got married, wife should use polite words to husband even she is elder than him.

"Polite things in language also appeared very much in other behavior in Korea. For example, at a convenience store in Korea, customer usually uses polite language to the shop’s person because they are not close. But it is a really strange thing to a Japanese because most Japanese thinks that customer has a strong advantage to the shop’s person and the customer usually doesn’t use polite words to the shop’s staff even if the customer is younger than the shop’s staff! Korean people have pay attention to use polite words or normal words even if very close person. And if the one suddenly use normally words to the other, it may be a little rude thing to the partner. And I think that there is a different appearance of polite meaning in conversation even if the Korean and Japanese are in same situation.

"The different thing among Japanese and Korean is as below thing: in Korean language, most polite meanings appeared in ‘what something is called and is also in the kind of verb used to the speaking partner. But in Japanese language, polite meaning sometimes appears only in a ‘what something is called’ without appearing in the verb. The relation of parents and children is one example of the situation. In Korean families, the children must use their parents by the proper form of address, but also they must use a term of respect in their verbs. Contrary to that, in Japanese families, although the children usually call their father ‘Otousan’ a meaning a polite word for a father in Japanese, children doesn’t use a verb of respect like ’saremasuka?’, the polite word for ‘do?’, to their parents. In this way, I felt that there are many points of difference between Japanese and Korean about 'polite' in conversation and behavior. I also feel that Japanese arrogant manner of a customer to the clerk is not so good thing and it is a sign that Japanese lose a little by little taking care of other person, I think. Maybe difference of politeness between Japan and Korea comes from strongness of Confucianism in Korea. Like that, I think that religion has a strong effect on one country's language. And apart from religion, like custom also strong effect on language. So Americans don't have terms of respect in language, even Koreans grown up in America.

"By the way, I was really surprised that the average English level of Korean students is very high. In Japan, I took TOEIC test and I usually gets a score of around 700-points. I noticed that in Korea, average skill of using English of Korean students is like me or higher than me! I think that it is higher than in Japan. But through English taking class in Korea, I knew that the student's skill is very high here! And they seems to have almost no difficulties to have a conversation with English speakers. I don't know why they are so skilled English even though maybe they don't have so many times to touch with English speakers compared to me. And I honestly felt that their hearing skill is averagely very high . For example, even when I can't understand the English teacher's order in English, almost every Korean student understood it after only one hearing. I felt that it is a sign of how Korea is using the power of English education compared to the Japanese."

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

English and free trade

This week I read an article in The Economist newspaper about Tseda Neeley, a professor at Harvard who believes all employees of multinational companies all over the world should be required to speak English. Her main reason is that it is more efficient. Whereas multilingualism is inefficient.

The Economist suggests that there may well be good reasons for international businesses using English. For example, it is the main language of science: nearly all influential scientific articles are written in or translated into English so that people all over the world can comment on and contribute to research. The newspaper also reminds us that many multinational companies began in English-speaking countries, including Britain, Australia and, above all, America. Moreover, English-speaking countries supply over 25% of the world’s GDP.

In Japan some companies already require all or many of their employees to use English. One of them is Nissan, which manufactures cars in 18 countries.

The policy started when the company went into partnership with the French car firm Renault in 1999. Since few Nissan workers speak French and few Renault employees speak Japanese, having English as the main working language largely avoids the need for translators.

Another example is the huge e-commerce company Rakuten. Although based in Japan, the company has connections all over the world. According The Economist, even the menus in the staff canteen are in English.

However, The Economist does not think it is a good idea to force employees use English. This London-based newspaper generally takes a free-market approach to the world, whether financial, social or cultural policies. As far as language goes, it argues that people may be motivated to learn English because of business opportunities, but there is no need to force them.

A lot of Japanese are forced to learn English nowadays, whether at work or at school. But I wonder how helpful this approach is.

Some linguists, such as Jean-Louis Calvet in France, compare languages to currencies and argue that some have more value in the marketplace than others. The question is whether we should interfere in the market or let exchanges take place freely.

Many people feel it is acceptable to interfere in markets in order to protect the weak and the small. In this sense perhaps there may some need to protect minority languages against the expansion of major languages like English, Spanish and Chinese. But it could also be said that making people use English whether they want to or not is an unnecessary interference in the market - on behalf of a currency that is already strong enough.

Or perhaps it is just a way of helping people deal with the needs of the global economy?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)